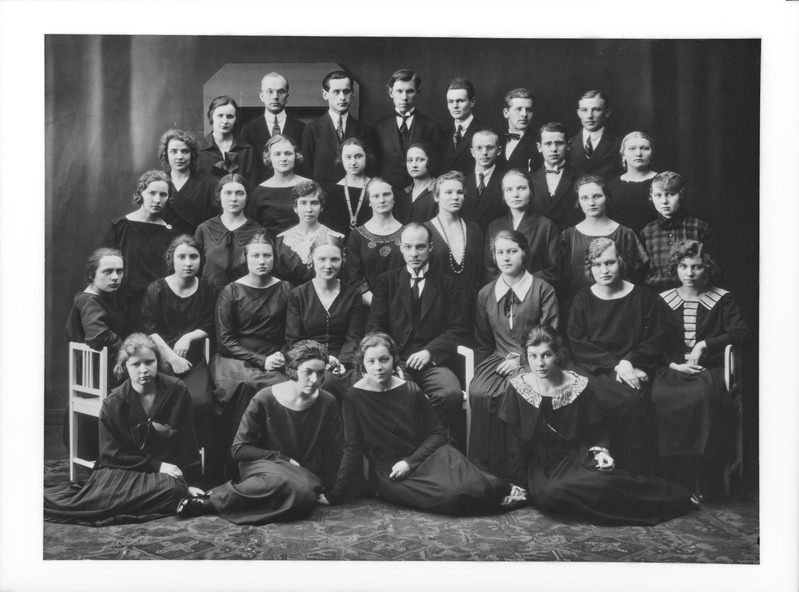

Estonian history has remarkable women who defied societal expectations to pursue careers in science and academia during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, further research is necessary to fully find out more about their stories. Nonetheless, some progress has been made in this respect, and a recent study by Janet Laidla (University of Tartu) and Lembi Anepaio (Tallinn University) identified over 30 women who earned doctoral degrees between 1904 and 1939.

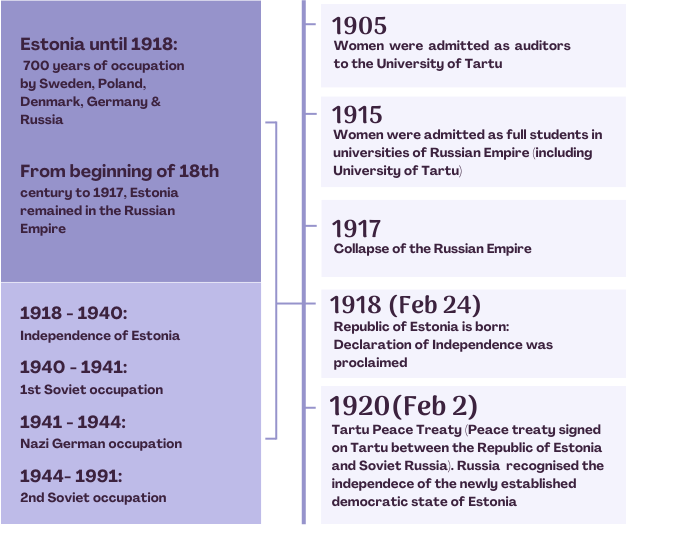

Women had been allowed to attend university as auditors in the Russian Empire since 1905, only to have this privilege revoked shortly afterwards. Instead, higher education courses for women were established throughout the Empire, including Tartu (Estonia). These courses provided women with an education as good as university’s, conducted mainly by the same lecturers, although it lacked official recognition. Many women from the Russian Empire migrated first to Zurich and Bern in Switzerland, and later to Germany, where women were allowed to defend their degrees during the early years of the 20th century. In fact, Lea Gutkin-Chaikis is considered the very first woman from present-day Estonia to have a PhD. She defended her degree in medicine in 1904 at the University of Freiburg in Germany. It is important to note that, before the First World War, a doctorate was the first qualification obtained at university in the German cultural sphere, just as a bachelor’s degree is today. However, the doctorate was not on a par with a modern bachelor’s degree, because the former was harder to obtain. From 1915 onwards, women were finally admitted as full students at universities in the Russian Empire.

Marta Schmiedelhelm (1896-1981) is the first example we would like to bring to you of a woman who earned recognition in the humanities during her era. She obtained her master’s degree in Philosophy in 1923 and completed her PhD in History at the University of Tartu in 1944, during the Nazi German occupation. Facing the Soviet authorities’ refusal to acknowledge her degree, she had to defend it again in 1956. Marta’s role as a conservator at the University of Tartu’s Archaeology Department exemplifies her defiance of social norms and her pioneering path in the scientific landscape of the early 20th century.

Liidia Poska-Teiss (1888-1956) is another example of Estonian women pioneer in science.2 In her case, within the field of the natural sciences. Liidia was born and raised in a privileged and influential family, providing her with the ideal environment to develop her academic ambitions. Her uncle, Jaan Poska, was Estonia’s first foreign minister.

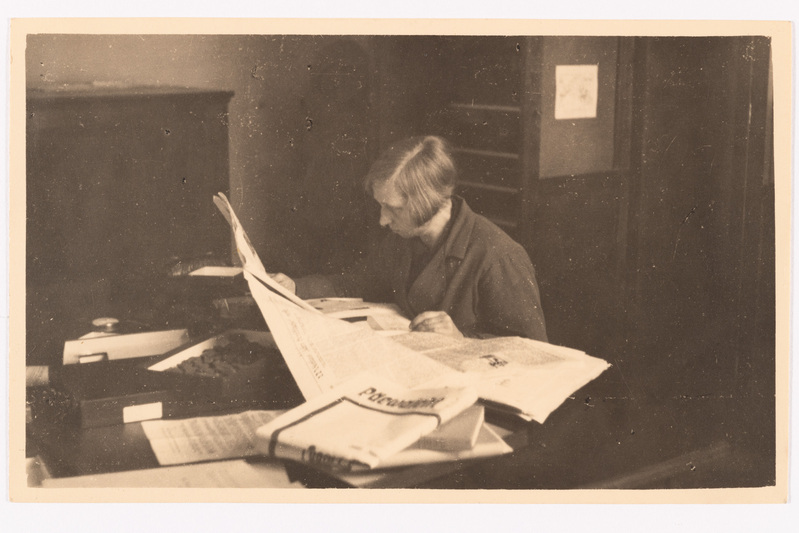

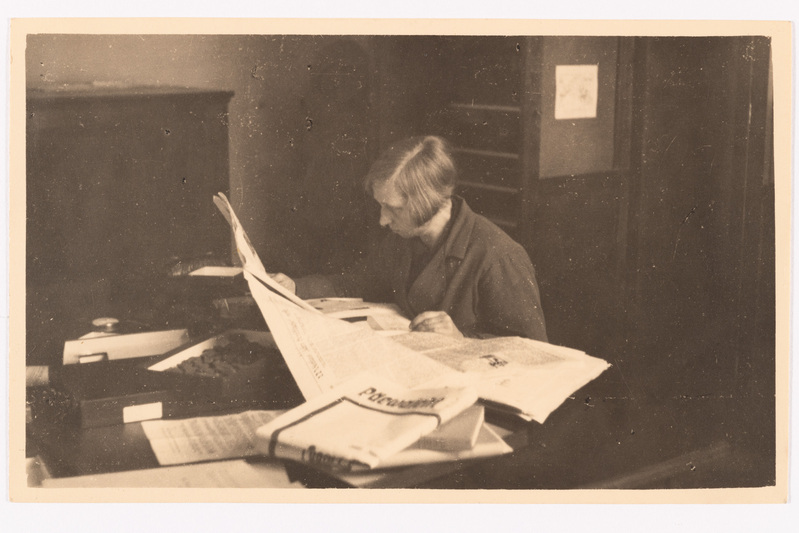

Liidia enrolled in the Higher Women’s Courses in Natural Sciences in St Petersburg, graduating in 1914. During and after her studies she started working, first in a laboratory as an aid of a histology assistant, and then as an assistant at the Institute of Psychoneurology in St Petersburg. Her work in these first years of her research career focused on the process of nuclei formation within epithelial cells located on the outer layer of the heart tissue. The Russian Revolution interrupted her research in St Petersburg and Lidia Poska-Teiss returned to Estonia. In May 1919 she wrote a letter directed to the University of Tartu, where she explained that she was keen to continue her research in histology, and in September of the same year, she got a position in the university as assistant to the Chair of Zoology.

After a trip to Berlin in 1923, she defended her PhD thesis in the University of Tartu in 1930 addressing debates on chromosome persistence. Despite political upheavals, she became an assistant professor in histology in 1939. Her career faced interruptions during the Soviet and German occupations, and in 1944 she became a professor at the Department of Darwinism and General Biology at the University of Tartu. Her field of research made her a target of ideological attacks during Stalinist campaigns, and she suffered from stress in her final years. Nonetheless, she inspired many disciples, contributing to the international recognition of Estonian research in cell and molecular biology.

Finally, we would like to share with you a bit of the story of Hilda Taba (1902-1967). Hilda was an influential Estonian-American educator and curriculum theorist known for her significant contributions to the field of education. She went to the United States in the early 1920s. She traveled there thanks to the Rockefeller scholarship program. During her time in the USA Taba pursued her studies, gaining an MA from the Bryn Mawr College and a PhD from the Columbia University Teachers College. In 1930 she applied to become a professor at the university of Tartu, but she was not elected. It has been argued that this decision might have been related to her gender. Some claim that because of this Hilda Taba returned to the USA. There she continued her academic career and made significant contributions to the field of education.

Hilda’s work primarily focused on curriculum development and instructional strategies. She developed a method of how to teach and approach the learner, known as the Taba Method. It involves a series of steps, including diagnosis of learners needs, formulation of objectives, organization of content, selection of learning experiences, and evaluation of outcomes. Taba’s approach emphasized the importance of understanding the learners’ cognitive development and of adapting the curriculum to their needs.

Throughout her career, Hilda Taba held various academic positions, including a teaching post at Columbia University and serving as a curriculum consultant for schools and educational organizations. She wrote several books and her work has had a lasting impact on curriculum theory and educational practices, influencing educators worldwide.

Research is still needed to fully recognise the enduring legacy of pioneering Estonian women in science. Nonetheless, we would like to reaffirm our commitment to gender equality and inclusion in science and academia by honoring the courage of the above scientist. May their determination and resilience continue to inspire future generations!

Refences

This blog post is partially based on the following articles and private conversations with Janet Laidla.

- Laidla, Janet; Anepaio, Lembi (2024). Esimesed doktorikraadiga naised tänapäeva Eesti aladelt [The First Female PhDs from the Present-day Estonian Area]. Õpetatud Eesti Seltsi aastaraamat / Annales Litterarum Societatis Esthonicae, 28−67.

- https://novaator.err.ee/1609218891/eesti-esimestest-naisdoktoritest-said-eeskatt-arstid-ja-opetajad

- https://feministeerium.ee/kes-oli-esimene-doktorikraadiga-eestlanna/

- https://doi.org/10.15157/tyak.v0i47.1618

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8132528/

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hilda-Taba

Special thanks to Maarja Eskla and María Benito for writing the text, and to Guillem Castañar Rubio and Virginia Rapún Mombiela for polishing the versions of the text in English and Spanish.